Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 01/02/2019 in all areas

-

2 points

-

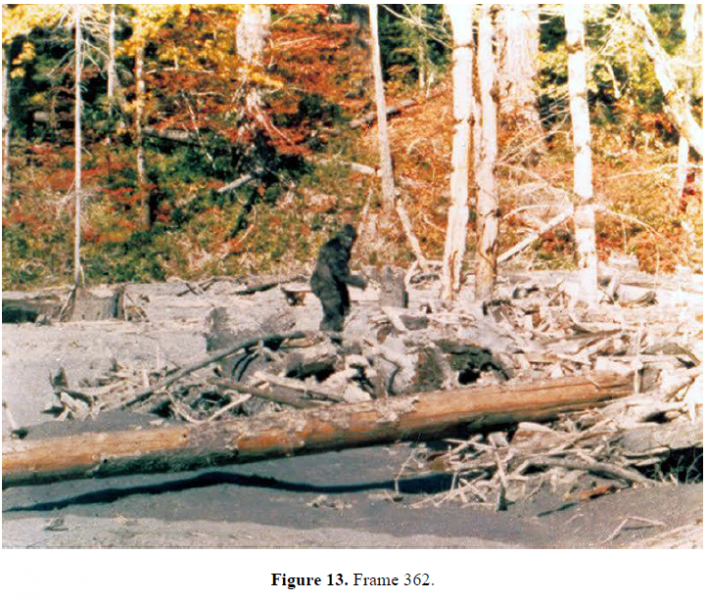

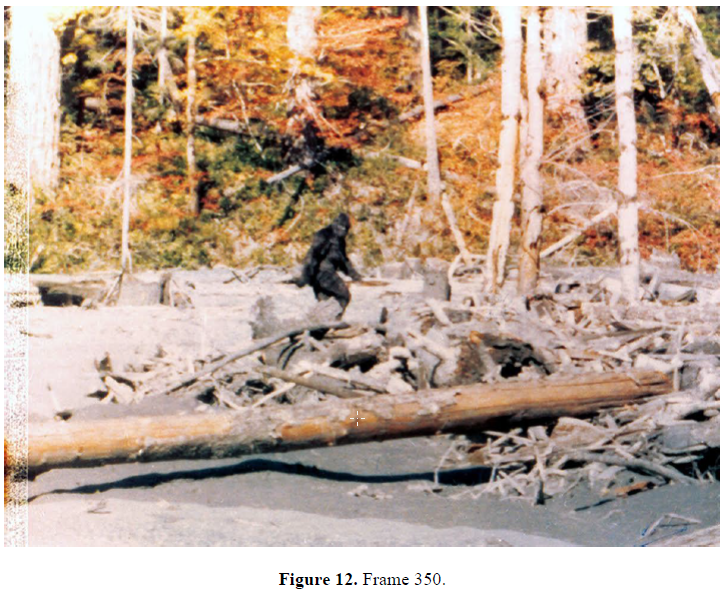

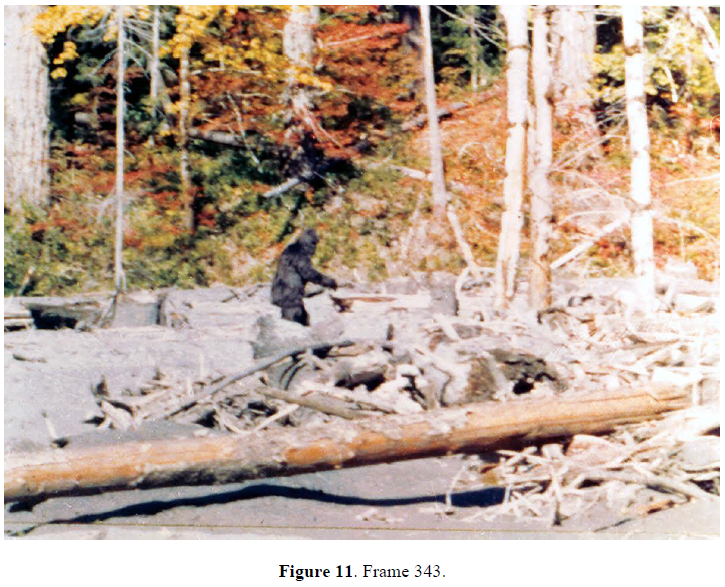

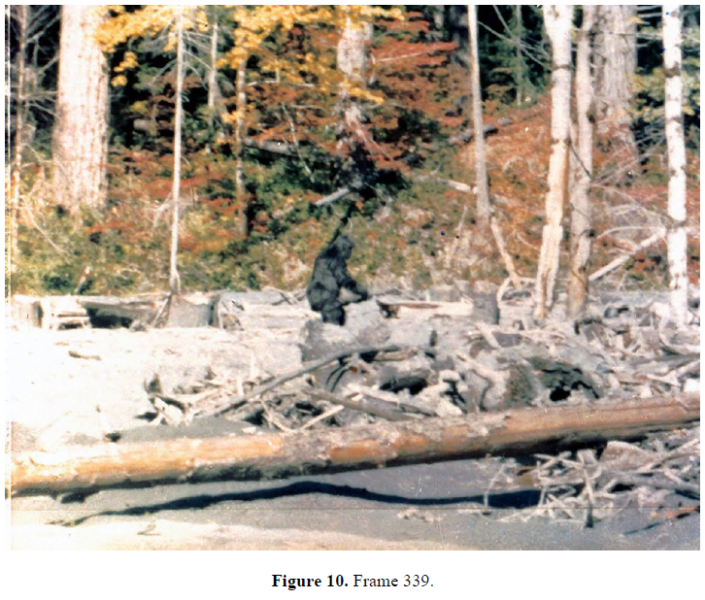

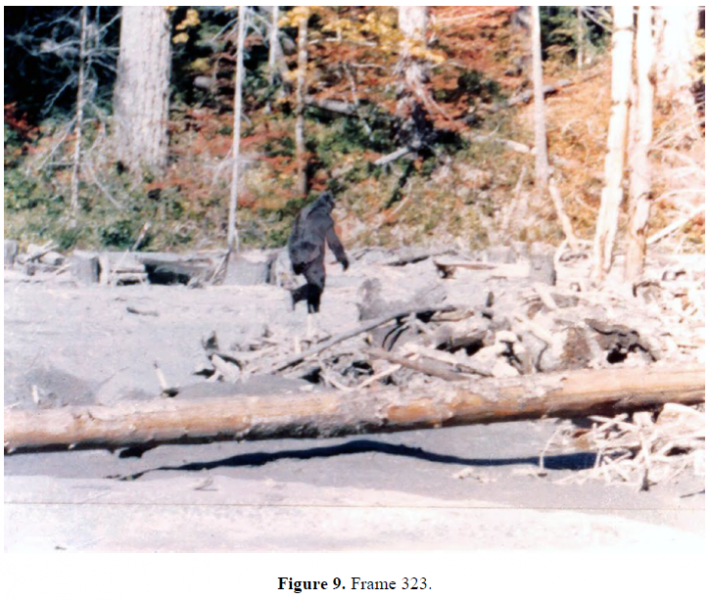

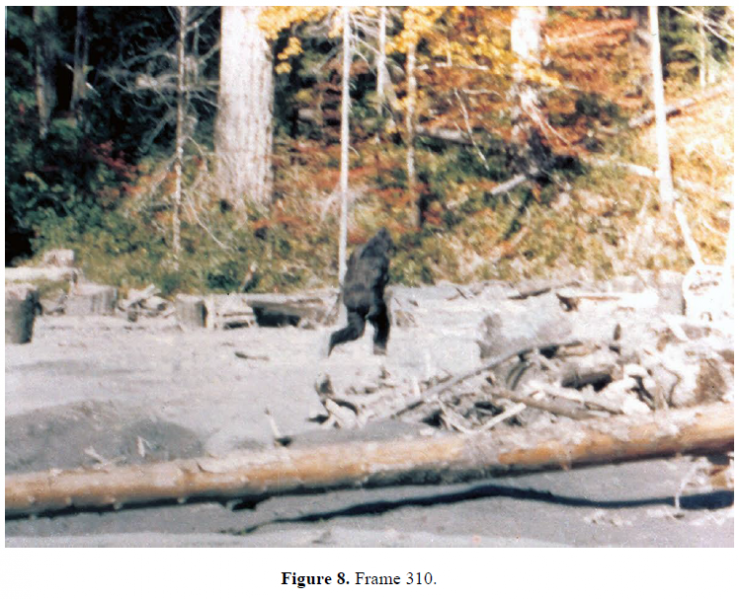

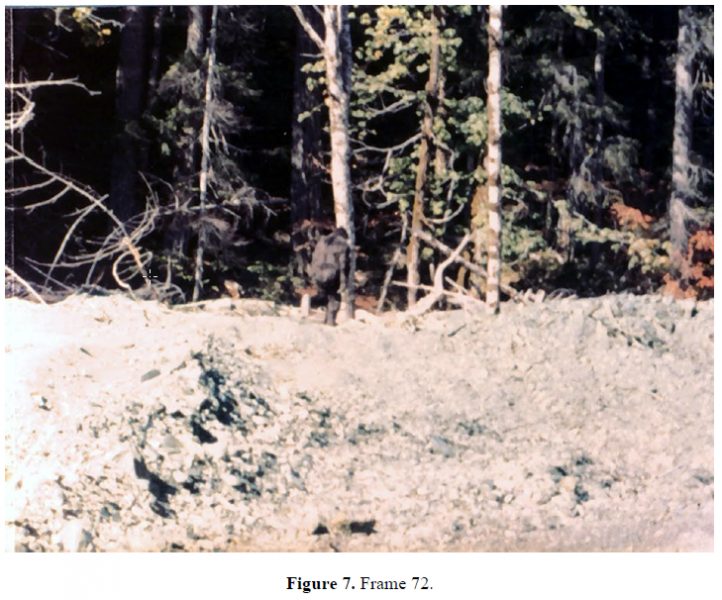

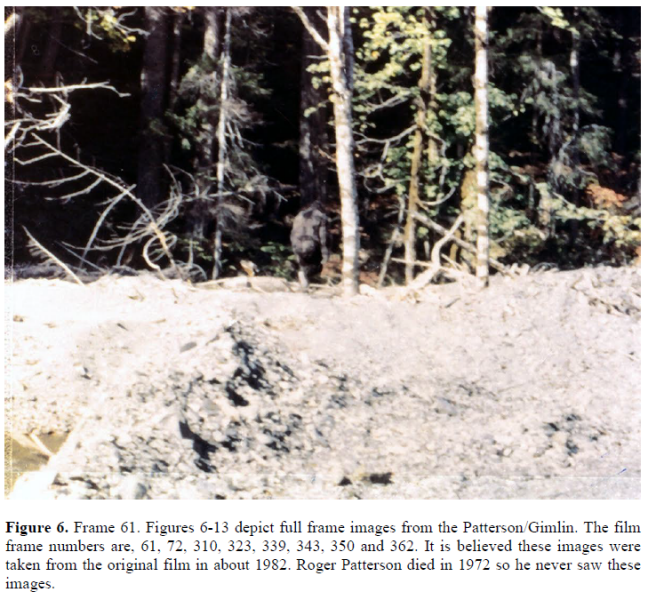

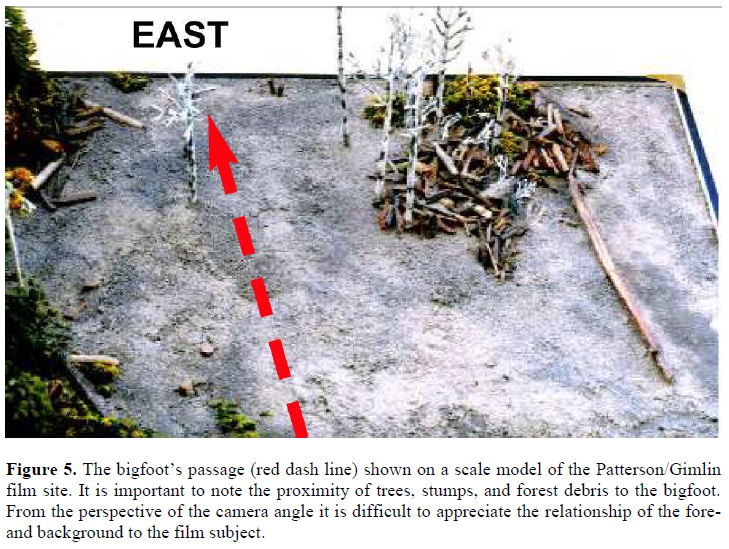

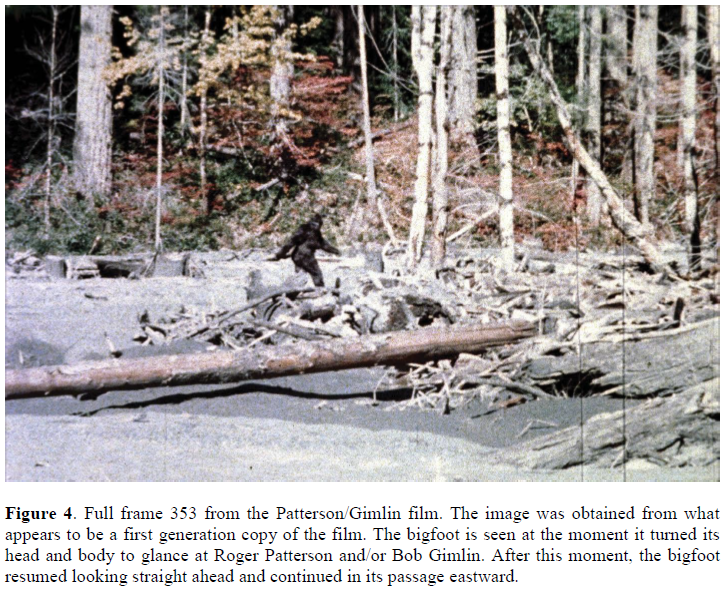

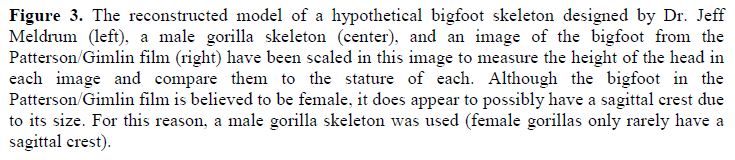

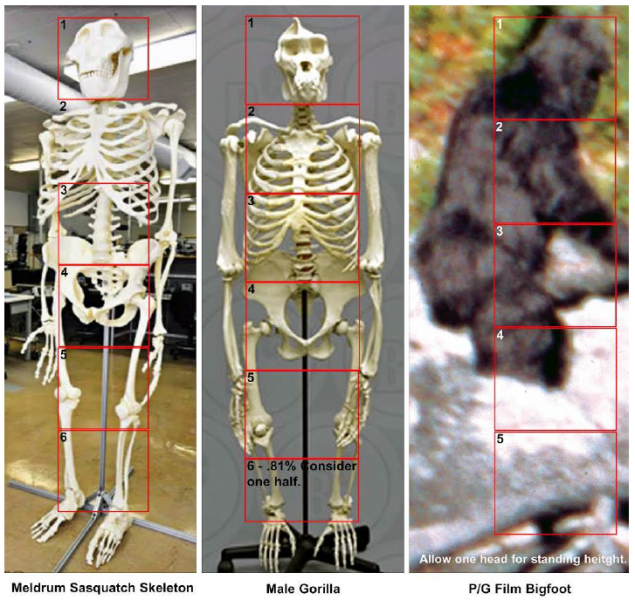

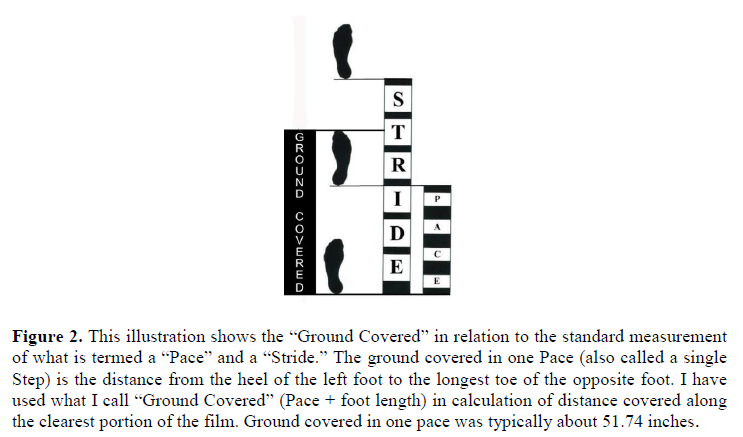

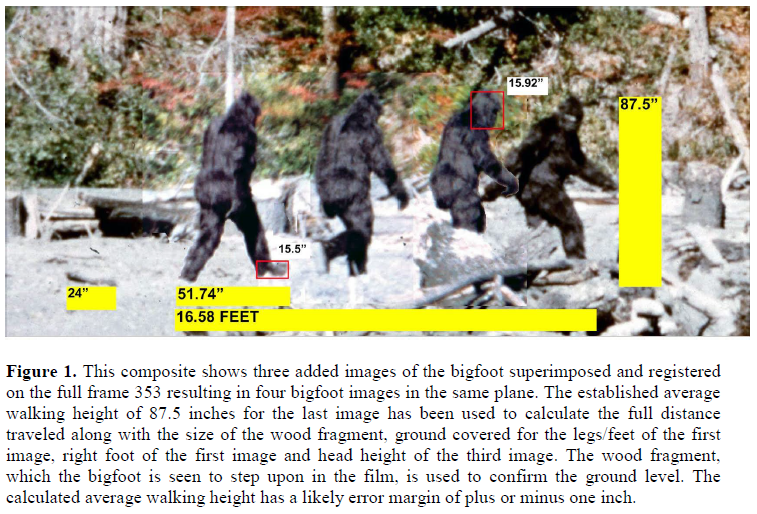

Reprinted with Permission 12/30/2018 The RELICT HOMINOID INQUIRY 6:1-16 (2017) Brief Communication THE PATTERSON/GIMLIN FILM – SOME NOTEWORTHY INSIGHTS Christopher Murphy* Vancouver, B.C., Canada ABSTRACT The motion picture film of an alleged bigfoot taken by Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin in October 1967 is examined and data are provided on the movement and stature of the bigfoot. It is seen that the film subject’s height and walking speed exceed that of the average human and that its head height to stature ratio is essentially beyond human proportions, being closer to that of an adult male gorilla. Quality full frame images from the film are presented to illustrate the level of detail captured by the film and witnessed by Patterson and Gimlin. *Correspondence to: Editor: meldd@isu.edu © RHI KEY WORDS: bigfoot, sasquatch, Bluff Creek, California, stature, film speed ------- Seen in Figure 1 is a composite of four film frames from the Patterson/Gimlin (P/G) film, selected from the range between frame 307 and frame 352 inclusive; encompassing a 46-frame sequence. The time duration for all of these frames to show on a screen is about 3 seconds. The distance covered by the subject in this time interval was about 16.6 feet. This means that the walking speed of the film subject was 3.85 miles per hour. The average walking speed of a human is 3.1 miles per hour (Browning et al, 2006). The alleged bigfoot was over 7 feet tall (Glickman, 1998), and despite its relatively short legs we can justify this inferred speed based on a camera speed of 16 frames per second. At one time, there was discussion that a camera speed of 24 frames per second could have been used. Had this been the case, the time interval for the 46 film fames reduces to 1.92 seconds and the walking speed increases to 6 miles per hour. In human terms, 6 miles per hour exceeds the preferred transition speed between jogging and running (4.5 mph, Raynor et al, 2006). It is evident in the film that the bigfoot is not jogging, confirming a camera speed of 16 frames per second. On the ground to the left of the subject in Figure 1, can be seen a wood fragment. René Dahinden identified and retrieved a wood fragment at about this spot at the film site in 1971. It measures 26.25 inches long. While the film frames in which the wood fragment are depicted are too blurry to conclusively determine its orientation and extremities to infer its length, we can reasonably conclude it is the same fragment. It can be used as an independent approximate scale to calculate the bigfoot’s maximum walking height as 87.5 inches. For the first image of the subject in Figure 1, I have measured the “ground covered” as the distance from heel to toe of the contralateral foot during a single pace (see Fig. 2). At 5 feet 11 inches, with a foot length of 11.5 inches, my “ground covered” comes out at 34 inches. If I were the same standing height as the film subject (~94 inches, since the subject walks with flexed limbs in a compliant gait, with a forward lean of approximately 5o), then it would be about 45 inches. If my feet were 15.5 inches long, then it would come out at 53 inches. In summary, a human 94 inches tall with 15.5 inch feet would cover the same ground in a single pace; obviously, the suggestion that this is merely an average man (70 inches tall) in a fur suit is untenable. I have also indicated the foot size for the first image of the film subject in Figure 1. The pair of casts made of the fresh footprints were 14.5 to 15 inches long (one foot is a bit larger -- humans often have the same condition, including myself). The foot length is reported here as 15.5 inches because one’s actual foot length is generally larger than footprint length. One of the reasons for that disparity is that a foot is measured from the back of the heel, not the end of the sole. For the third image of the film subject in Figure 1, I have shown the vertical height of the head. Given the bigfoot standing height of 94 inches, the bigfoot is about 5.9 heads tall. Human adults are generally 7.5 to 8 heads tall. In my opinion, the size and proportion of the film subject’s head should be added to the other measurements and proportions that are essentially beyond human standards, (i.e., arm and leg lengths; Meldrum 2006). I note that Dr. Jeff Meldrum used 6 heads high for the stature of the sasquatch skeleton recon-struction he consulted on, which was based on the Patterson/Gimlin film subject (Committee Films, 2015). The measurement for a male gorilla specimen is 5.5 heads. This puts the sasquatch between gorilla and human values. The illustrations in Figure 3 contrast the relative head height in relation to stature in Meldrum’s skeletal reconstruction (Mitchell, 2015), a male gorilla (Bone Clones specimen), and the Patterson/Gimlin film subject. The P/G film image shows the walking height, so one head height should be added to accommodate comparisons with standing heights of other specimens. I need to mention that back in the days when we had to use an actual printed photograph and a metal ruler for measurements, the results were generally less accurate. Dr. Meldrum challenged one of my illustrations for this reason. He was right and his words still echo in my head. However, time has moved on and computers have replaced rulers and printed photographs. The values presented in this paper have greater precision and accuracy, with only a relatively small margin of error due in part to photographic perspective. This margin is insignificant relative to the absolute scale of the proportions we are dealing with. Figure 4 is a superior image of frame 353 (1/16th of second after the highly publicized frame 352). The scope of the frame gives you a good idea of the total distance the bigfoot traveled for the main part of the film, from which the clearest images have been obtained. It is not much more than about 40 feet. Frame 364 is the last best image. It is not even one second after frame 353. Once the film subject gets to the leaning tree on the right of the frame, it turns left, heading generally north-ward, providing a view of its back side. Keep in mind that there is nothing immediately close to the film subject, as it crosses the 40-foot eastward stretch. All the debris and trees are many feet away. If the film were taken from the left (in back of and above the bigfoot) then the scene would look as depicted in Figure 5, with the red dashed- line indicating the line of travel of the bigfoot. There is thick forest to the north and east. Bluff Creek is to the south. Patterson pursued the bigfoot from the south and west. Its passage was clear, but since Patterson was running, motion blur renders most of these film frames not useful. He stopped south of the big downed log seen in the foreground and captured about 6 seconds of film without any taller obstructions in the foreground. The most interesting images from the P/G film are what are called here the “full frames.” They are intriguing because they show what Patterson saw as he peered through the view finder on his movie camera (although what he saw was much smaller). Real photographic prints were produced for the 12 clearest frames, but only 8 survived into the 1990s (Fig. 6 through 13). Frame 352 was among those that disappeared. What we see in this frame print and that for frame 353, came from, or were derived from, an entirely different source. It is believed the photos were pro-duced in about 1982 from the original film, and a short time after that the eight photos I have were locked in a very large safe, to which the combination was lost. The safe was reopened in the early 1990s. The originals are somewhat faded and there is a little damage on one photograph, now corrected. After the first two images (Fig. 6, 7), the bigfoot went into the tree line and was only partially visible through the tree trunks and bushes. It then came out into a reasonably clear section on the sand bar, but no good images resulted until it arrived at the clear section where Patterson knelt and took reasonably steady movie footage. He moved up to the downed log at about the time the bigfoot got to the second tree seen frame right. After this point, all the images are partially blocked by the trees, until the subject was some distance farther away and provided only parting shots from behind, before disappearing into the debris upstream. What Patterson saw through the camera view finder was likely about the size of the image shown here (below). This is why he was not certain that he had indeed captured the bigfoot on film. So he arranged to ship the exposed film to his brother-in-law to develop and determine what was there before the two men (Patterson and Gimlin) left the area. As Gimlin was looking at the bigfoot directly, he would have seen it more clearly than Patterson, but naturally he had no idea of what Patterson caught on film. Had Patterson used a current-day consumer-grade video camera all we would see is a pixelated “blob squatch” with minimal detail, and limited potential for enlargement. Now there are digital video cameras that could have produced the same or even better images, albeit such cameras would have been too expensive for Patterson to have acquired, had they been available at that time. Whatever the case, we are fortunate that Patterson used a movie camera and what was considered the best film stock of that period, producing images capable of considerable enlargement and enhancement by means of modern digital technologies. At this writing, we are nearing 50 years since Patterson took the film. Few of the still images were published until 37 years later (Murphy, 2004). Lots of material, including scientific commentaries, were written, but none were illustrated with the images you see in this paper. Without getting into the reasons for this, suffice it to say it had unfortunate consequences. We might reason that had more quality images been published early on, the scientific community would have paid greater attention to the film. Even Dr. Grover Krantz could not publish all the full quality images in his landmark book (Krantz, 1999). The advent of the Internet provided some opportunity for dissemination of images, but that really came too late to have any significant impact before the bigfoot phenomenon was labeled as a tabloid subject by the scientific community and discounted. The film was dismissed as too blurry and shaky to be of any scientific merit in the absence of a specimen, or simply that it was all too obviously merely a man-in-a-fur-suit. Perhaps the publication of this paper on the occasion of the 50th anniversary year of the Patterson/Gimlin film event will draw renewed attention to the scientific merits of this most intriguing photographic evidence for the existence of a relict hominoid in North America. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Dr. Jeff Meldrum for his great assistance and advice in the preparation of this paper. Also, I wish to acknowledge Jeff Glickman, the forensic scientist who performed the first full and complete analysis of the Patterson/Gimlin film (Toward a Resolution of the Bigfoot Phenomenon, 1998). His remarkable work never ceases to amaze me. To this day it has never been equaled. LITERATURE CITED Bone Clones, Inc., Osteological Replications: Current Catalog. Canoga Park, California, USA. Browning RC, Baker EA, Herron JA and Kram R (2006). Effects of obesity and sex on the energetic cost and preferred speed of walking. Journal of Applied Physiology. 100(2):390–398. Committee Films (2015) Sasquatch Captured, The History Channel. Glickman J (1998) Toward a Resolution of the Bigfoot Phenomenon. Hood River, Oregon: North American Science Institute. Krantz, GS (1999) Bigfoot/Sasquatch Evidence, Surrey,BC, Canada: Hancock House Publishers. Mitchell P (2015) http://isubengal.com/sixteen-hun-dred-hours-of-sasquatch-skeleton/ Meldrum J (2006) Sasquatch : Legend Meets Science. New York: Doherty Publishers. Murphy, CL (2004) Meet the Sasquatch. Surrey, BC, Canada: Hancock House Publishers. Raynor AJ; Yi CJ; Abernethy B; Jong QJ (2002). Are transitions in human gait determined by mechanical, kinetic or energetic factors? Human Movement Science. 21(5–6):785–805. ------ Christopher L. Murphy retired from the British Columbia Telephone Company (now Telus) in 1994. He worked in Supply Operations and became highly involved in industrial engineering and management processes. He authored books on business management and lectured throughout Canada. He obtained certification from the University of British Columbia in Management Development and taught night school at the British Columbia Institute of Technology. A member of the Masonic Order and avid philatelist, Chris became president of the Masonic Stamp Club of New York in 2000. He wrote two books on Masonic Philately and was recognized as a Masonic author in 1995. His interest in the sasquatch commenced in 1993 and he has since authored several books on this subject, including Know the Sasquatch/Bigfoot (2010). He collected sasquatch-related artifacts and other items and curated a sasquatch exhibit at the Museum of Vancouver in 2004/5. The exhibit has since traveled to six other public museums in Canada and the USA. -----1 point

-

Hi All...I used to be on these forums quite a few years ago, from 2004-2012? I was Sailgirl. I decided to come back to this site. I am from WI. I have been researching Bigfoot since around 1986. I have done quite a bit of my own research in the backwoods of Northern/North Central WI. I have seen 14" prints with 5 toes. I have heard whoops as well. No visual sightings though.1 point

-

There are many followers of Elmer Keith. Handgun hunting was "the thing" in 60s, 70s, and 80s. It was considered to be the next level of difficulty among those that had already bagged the full list of North American big game with a rifle. Almost all of the handgun hunters I've known over the years, including myself, used magnum handguns with 8 inch or better barrels or a T/C with a 12 to 14 inch barrel chambered for a rifle cartridge. Getting inside of 50 yards was the goal. Anything outside of that was considered unsportsmanlike as the hunter was unlikely to be able to put a bullet in the kill zone of the animal. Later, the max range was determined by how far away you could put 5 consecutive shots on a paper plate. For some, it was 20 yards, for others it was 110 yards. While a handgun is as intrinsically as accurate as a rifle, the short sight radius and considerably higher power drop-off makes handgun hunting extremely challenging and extremely rewarding. However, given my tired old eyes, I can't even see a whitetail beyond a hundred yards, much less be able to put a bullet in the magic triangle with a handgun. LOL Well, maybe with a scoped T/C in .30-.30.1 point

-

When I was hiking yesterday, I felt like I was being watched. I kept looking all around me when I came upon the first track. There's a track way that I recorded with my cam corder that goes up the mountain side just to the left of this side creek which I haven't uploaded yet. Anyways I posted one of those photos yesterday looking towards where I felt I was being watched. After zooming in on the photo, there appears to be what looks like a sasquatch standing behind a pine tree looking right at me, just like the one I captured on video back around the same time of year back in 2016 a few miles away. These Bigfoot's blend in so incredibly well. Here's the photo and a couple of zoomed in photo with different lighting. I can see what appears to be a bottom right leg along with his upper body and face. It was getting late on a overcast day with some light snow flurries. I was hesitant to post this knowing the clarity isn't all that great being the photo was taken with my smart phone, but here it is.1 point

This leaderboard is set to New York/GMT-05:00